Going Viral: How Digital Headlines Framed the start of the COVID-19 Pandemic

On March 11, 2020, a single sentence from the World Health Organization director rippled across the internet: “We have therefore made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic.” The statement further went on to state the alleged number of active cases and deaths and then highlighted the severity of the situation, “Pandemic is not a word to use lightly or carelessly. It is a word that, if misused, can cause unreasonable fear, or unjustified acceptance that the fight is over, leading to unnecessary suffering and death.” This statement and labeling of COVID-19 as a pandemic was globally significant, as a pandemic had never been started by the coronavirus and was a worldwide call for all countries to take urgent and aggressive action. The label “pandemic” prompted formal recognition that the illness was an uncontrolled worldwide crisis that was spreading rapidly and triggered mobilization of resources all across the globe from doctors and scientists. Globally, private and public funders launched into looking for answers regarding the viral genetics, immunopathogenesis and therapeutic strategies.

Digital pandemic messages – how information was spread

- Official websites and email services (Health Canada and WHO) provided reliable and accessible updates regarding case numbers, regulations, and advisories

- Mobile Health Apps (NHS covid-19 app and ZOE) used features such as contact tracing, symptom reporting and vaccine management for surveillance of the pandemic

- Social Media (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook) was utilized by many health authorities to rapidly spread information to the mass public

Headlines

- BBC News – “Coronavirus: UK deaths rise to 144 as PM orders pubs and restaurants to shut”

- CNN – “Trump warns of ‘painful’ two weeks ahead as White House projects more than 100,000 coronavirus deaths”

- New York Times – “A New York Doctor’s Coronavirus Warning: The Sky Is Falling”

- New York Times – “At War With No Ammo’: Doctors Say Shortage of Protective Gear Is Dire”

So, why do these headlines matter? During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, headlines played a major role in shaping public perception, emotional response, and behavioral outcomes. The headlines from BBC, CNN, and the New York Times highlight emotional language using words such as “dire,” “war,” “deaths,” and “painful.” Major outlets used alarmist language to signal urgency and cause disruption. COVID-19 alarming headlines did more than simply grab the attention of the reader. Research has showed that fear based headlines increase perceived risk of illness but also simultaneously reduce preventative behaviours (Kim et al., 2024). Emotional fatigue, distrust, and defensive avoidance are common psychological responses to alarmist language, which can undermine public health goals. Another study found that COVID-19 headlines evoked strong negative emotions, especially fear and anxiety, which shaped public discourse and trust in health messaging (Rufai & Bunce, 2020). The use of alarmist language during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about media responsibility and accountability when influencing the public.

What went viral:

This tweet was reposted over 50,000 times and marked the formal shift in global framing. It triggered emergency press conferences made in countries such as Canada, USA, UK, and Australia. Further, the stock market plunged, schools shut down, the streets deserted, and hospitals became packed. Major health policies came shortly after this tweet including travel bans, school closures, and funding announcements including Canada’s one billion COVID-19 response fund. The public interpreted this as a signal that normal life was over. Some anonymous tweets from the general public include themes such as

Sarcasm and disbelief “So now it’s officially a pandemic? Cool cool cool. Guess I’ll cancel my imaginary vacation.” , “WHO finally called it a pandemic. Took long enough.”

Calls for accountability “This should’ve been declared weeks ago. We wasted precious time.”

Emotional reactivity ““I’m scared. I don’t know what this means for my family.” ,“This is surreal. Stay safe everyone.”

Tom Hanks tweet that he and his wife had been diagnosed with COVID-19 went viral globally. It was cited by numerous news outlets and was liked and retweeted extensively. This went viral due to the fact that Tom Hanks is seen as universally relatable and trustworthy. He was genreally unproblamatic and universally known, which made his diagnosis feel personal and real, especially to citizens in the US and Canada. Penn State conducted a study on the effects of Hank’s tweet and found that it shaped public understand and behaviour, increasing awareness and concern of the virus.

This is an example of “important” events that occurred during the beginning of the pandemic that shaped media and public perceptions of the virus. As discussed Tom Hank’s diagnosis was a viral event. Furthermore, the NBA shutting down was also a significant event. As a few players had tested positive the league had decided to suspend the games. This event was another one that hit the public with a brutal reality, this virus was real, and it was coming to affect every single part of everyday life.

Shifting Narratives – From Panic to Adaption

In the days following the WHO’s pandemic declaration on March 11, 2020, global media erupted with alarmist headlines. News outlets like CNN, BBC, and The New York Times emphasized death tolls, lockdowns, and economic collapse. The tone was urgent, emotional, and often overwhelming. This initial phase of panic was marked by phrases like “the sky is falling,” “painful weeks ahead,” and “unprecedented shutdowns,” which dominated front pages and social media feeds

But within weeks, the narrative began to shift. Mach et al., (2021) highlights that governments and health agencies rolled out containment strategies, media coverage pivoted toward prevention. One of the most iconic examples was the emergence of the “flatten the curve” graphic which was a simple infographic adapted from academic sources and widely circulated by journalists, scientists, and public health officials.

By late March and early April, coverage began to emphasize community solidarity. Stories of frontline workers, mutual aid networks, and creative coping strategies gained traction. Hashtags like #StayHome and #TogetherApart reflected a growing sense of shared responsibility. According to a study from MacEwan University, Canada’s communication strategy during this period emphasized transparency, credible spokespeople, and culturally sensitive messaging

However, as the pandemic dragged on, a new phase emerged, fatigue. By May 2020, media coverage began to decline even as cases surged. The Lancet noted that despite worsening conditions, public attention waned and headlines became less frequent and less urgent. This fatigue was mirrored in public behavior, with declining compliance and rising frustration.

This evolution from panic to prevention, solidarity, and fatigue reveals the power and responsibility of media and headlines in shaping public understanding. Early alarmist coverage may have spurred action, but it also risked emotional burnout, mass fear and distrust. As communication continued, it became more informative, and visual. The “flatten the curve” campaign exemplified how clear, empathetic messaging can influence behavior without inducing panic in the general public.

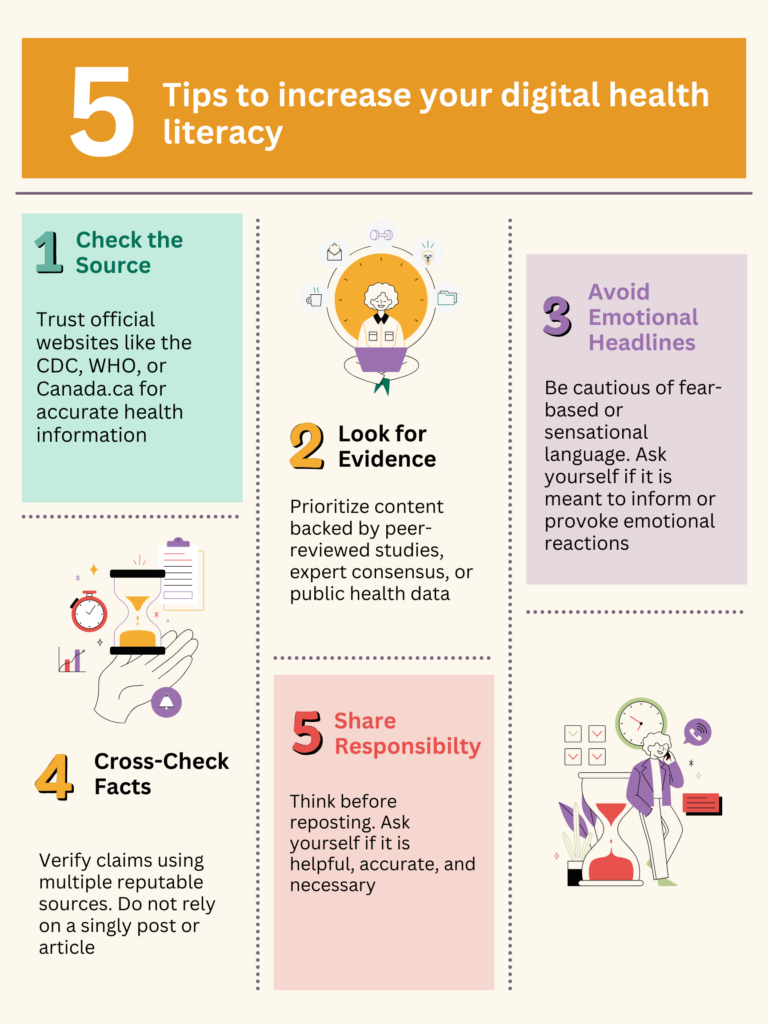

Finally, I will leave you with 5 tips for increasing your digital health literacy that may help you decipher and critically analyze headlines and articles with health related information.